Mending Fences by Susan Wingert

- Jul 29, 2024

- 7 min read

My mother’s request was not unreasonable. She wanted a fence. She wanted a fence to keep the dog in and the rabbits out. She wanted my father to build it. After a parade of seasons, the gate was the only thing standing. In my father’s defence, it was the sturdiest gate anyone had ever built — he had encased it on three sides in a foot and a half of concrete. Unfortunately, on account of the price of concrete, there was no money left for the rest of it.

My mother, with her underwear peekabooing through a hole in the waistband of her grey sweats, stepped over Lucky’s tie out, which was flopped across the steps like a used party streamer, and marched across the parched lawn. In her hand, she clutched a piece of looseleaf that waved in the breeze as though she were signalling her surrender. It was quite the opposite.

Shots were about to be fired.

She knelt in front of the gate, as if ready for prayer, fiddling with the chain link and the paper. Then, like a sinner who had repented, she rose and strode back to the house with her nose pointed to the sky. I waited, crouched in the droopy fringes of the old willow tree, until I heard the screen door bang.

Inchmeal, I lowered myself to the ground, careful not to scrape the tender flesh of my thigh on the raspy tree bark. I skulked my way to the spot where my mother had knelt. There, fastened indelibly to the chain link, was the tarnished lock we used to keep our possessions safe from thieves at the community pool. The note, in my mother’s perfect penmanship, read: I imagined there would be a fence here. You imagined this would last. It’s over. I’m sorry. I just can’t anymore.

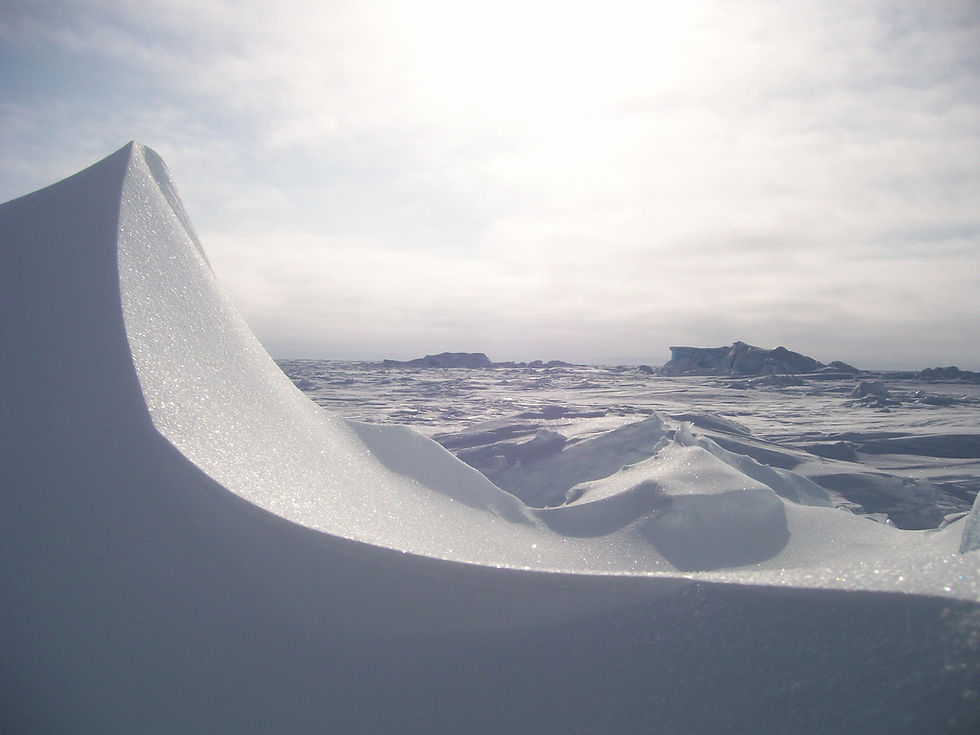

In that moment of discovery most horrible, I felt as though someone had poured a bucket of newly thawed creek water over me. The warmth of my body never to return. As the cold ebbed, the flush in my cheeks flowed. My stomach started whirring like a milkshake blender. My knees left my body entirely. What would Papito say? What would happen to us? Would I end up like Oliver Twist and have to join a gang to survive? I tenderly touched the spot where the teardrop tattoo would sit.

Why couldn’t my father build a normal fence like Ainsley Higgins’s dad? Mr. Higgins spent the entire weekend in cargo shorts and steel toes digging holes, then pouring a dollop of concrete into each before sinking impeccably spaced posts, checking the level after each one. Every so often, he would crack open a can of Bud Light, stand back, and admire his handiwork.

My dad, on the other hand, seemed to be paying homage to the opulent stone and wrought iron gates from his childhood in Mexico, except that we couldn’t afford a single piece of stone or iron, let alone the grand estate. What I knew for certain was that I couldn’t be standing there when my father arrived. I mustered my resolve and commanded my knees to return to active duty and get me out of there. Obediently, they flapped my feet up and down as we hightailed it to the safety of the musty metal shed.

Just as the sun turned golden, I heard the distant whistling of Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go, accompanied by the jingle of a metal lunchbox keeping time. My father. Was coming.

Maybe the note would self-destruct in five seconds like they did on Mission Impossible? He didn’t need to know. Nothing had to change. I wanted to run out. Steer him towards a game of catch. Or bamboozle him into repairing the chain on my brother’s bike. Instead, I stayed, like the coward I was, shielded from the laser beams of pain I knew the note would unleash. I hoped beyond hope that the infernal thumping of my heart wouldn’t give me away. I peeked through the crack in the door, careful to keep my body out of view.

At first, my father made like he was going to walk right past the gate but, just as it was passing out of his peripheral vision, he stopped. And turned. He squinted at the paper flapping there like a lame bird. He plucked it from the lock and read it, at least three times by my count. He looked helplessly toward the house, but it merely peered back through shutters of peeling brown paint. He ran his hand through his dark curls, gripping them hard as he pulled his hand forward toward his face, letting it trail down his neck, head tilted to the sky. He looked back at the house as though he were a hungry child, and it were a bakery. He set down his lunchbox and sank to the ground, his back sliding along his beloved gate.

My heart longed to run to him, submerge myself beside him in the mud, let my shoes squish into it, even if it meant my mother would make me strip at the front door. I was desperate to wrap myself around him, which I could now do because I had grown over the winter. But, before I could convince dread to release me from its clutches, my sweet papito stood up, dusted off his work pants, kissed his fingers, pressed them toward the house, and turned back down the gravel road to town.

From then on, the Sunday after each payday, if the ground were not frozen, he returned to the house and built one section of fence. Then, he would take me and my brother for ice cream or to the movies. He finished the fence near the end of the second summer. On that day, my mother invited him in for dinner — Sloppy Joes and cream corn.

In the doorway with the cool, smoke-tinged night air wafting in, my father leaned in and gave my mother a kiss on her cheek, saying, “Thank you for the invitation. I have missed this.”

My mother, quite to my surprise, didn’t pull away or furrow her brow. Instead, she smiled back at him and said, “It was nice to have you here. The kids missed you.”

As my father turned to leave, my mother called after him, “Why don’t you come again next Sunday?”

He looked back at her with a smile that could not mask the welling of his eyes. “I’d like that very much.”

Lucky, as though doing a dance of praise from her tail to her head, gleefully followed him outside into her newly enclosed queendom. She grabbed a grungy tennis ball from the ground and bounded a full victory lap. My heart did the same. Like Luke Skywalker, I was going to be the chosen one who would save my family from the evil empire of divorce. This singular, electric thought kept my mind marching far above the tempo required for sleep until well after all the creatures of the night, frogs and toads and owls, had welcomed the Sandman in.

My father came that Sunday dressed in the only button-up shirt he owned and his knock-off Levi’s. I waited feverishly for a love inferno to ignite over plates of clearance-priced porkchops. And still, much to my disappointment, my parents maintained their holding pattern around each other.

The next Sunday, he came heaving a bag of dog food. My mother gushed and praised his thoughtfulness. The Sunday after that and the one after that and the Sunday after that followed the same tired pattern: perfectly pleasant but he did not, as Harlequin Romances had convinced me was very common, rip his shirt open and take her into a passionate embrace. I was wholly convinced, right down to my toenails, next week would be the one.

One dreary Sunday in November, when winter seemed coiled and ready to pounce, my papito didn’t show. With pot roast growing cold on our plates, my brother and I tried to divine his whereabouts like witches staring into a cauldron.

“Maybe he had to go back in time to save the world from aliens or the Nazis?” my brother offered.

I was old enough to know time travel was something they made up in the 1960s. I went to bed with a weight in my chest and an ache in my bones. Had he given up on us? Had my mother screwed it up with her tepid response to his dog-food-laden overtures?

I languidly resisted the first vestiges of light, which streamed from the crack in my copper-colored curtains directly into my left eye. The sun’s efforts were soon aided by my mother whose efforts to wake me felt like a rolling pin on dough.

“You are going to be late if you don’t get going, young lady.”

I rolled myself upright and put on the first thing I plucked from the laundry basket before heading downstairs. My mother, in her vain attempts to keep our kitchen from returning to the wild, was clattering dishes and wiping sticky spots. She plunked a bowl of Cheerios in front of me. I shovelled in a mouthful and settled into the monotony of chewing.

I now wish I had savored that moment. The one before the gun goes off and everything changes. In our case, it wasn’t a gun, but the phone, that ended my world.

As it belted out a frantic baaaaarrrringggg, my mother glanced at my brother and then me through the corner of her eye before letting out a small sigh and plucking the phone from the cradle.

“Hello?” She listened. “Yes. That’s me.” Silence. My mother breathed in slowly. My brother and I watched each muscle, one by one like dominos, constrict around this news. No breath moved in or out. I felt my body suspended in the same space as hers. I waited. I waited. Expectantly. For her to declare, No thank you. We don’t need our ducts cleaned.

Instead, she whispered, “Oh god.” And all the dominos seemed to collapse at once. She nodded her head and gave some cursory yes, yeses, and several I understands before hanging up the phone.

My mother didn’t look at us. She didn’t make a sound. She drifted out the door, pulling her sweater tightly around her, arms crossed around her waist. She meandered across the still parched lawn until she reached the gate and its one and a half feet of concrete. She reached out her hand and caressed the fence posts. One by one.

Comments